Carry On... #Inevitable Nuclear Armageddon

Last week in our Halloween-themed film we saw Orson Welles and his Mercury Theatre troupe destroy the world in front of a terrified radio audience.

As one might expect, there was a great deal of soul-searching by the media in the days and weeks that followed. Some journalists were fascinated by the panic, some obsessed over the implications, and some were openly contemptuous of anyone gullible enough to believe that Martians were invading New Jersey.

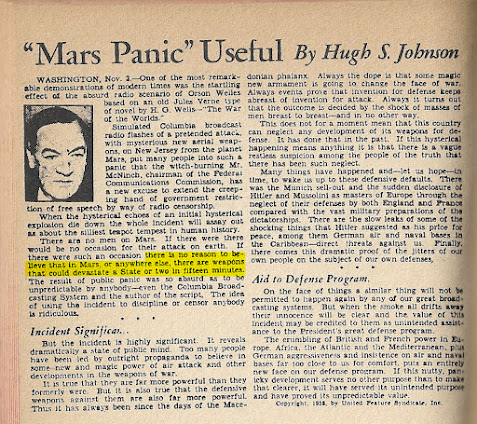

Hugh S. Johnson, a free-lance journalist (and former associate of President Roosevelt) wrote a particularly scathing diatribe in which he wryly noted that "there is no reason to believe that in Mars, or anywhere else, there are weapons that could devastate a State or two in fifteen minutes."

He made this observation in November, 1938.

He was partially correct. Such weapons took a lot less than 15 minutes, and they didn't come from Mars.

They came from Manhattan.

Before becoming a journalist, Hugh S. Johnson had been one of the architects of Roosevelt's "New Deal" and a driving force behind the National Recovery Act. By 1938 he had fallen out with Roosevelt, and was presumably no longer a Government insider. He eventually died in April, 1942; a few months before the founding of a little endeavour called The Manhattan Project. Had he lived just a few years longer, he would have witnessed (along with the rest of the world) the total annihilation of two Japanese cities by a completely new and unthinkable type of weapon.

A weapon that had not come from Mars.

World War One was frequently referred to as the "War to End All Wars" (although it was hardly ever called that in hindsight). That term was originally coined by (of all people) H.G. Wells, in one of his less accurate predictions (sorry; spoilers) and it reflected a sense that the 1914-18 war was a new kind of conflict; one that was going to fundamentally alter our attitudes towards war.

It is, I think, significant that absolutely no one at any point was ever tempted to refer to World War Two as The War to End Wars. The radioactive dust had barely settled on the apocalyptic wastelands that used to be Hiroshima and Nagasaki before the superpowers of the world were positioning themselves for the next grand conflict. It was a generally held perception (eagerly endorsed by various Governments) that World War Three was inevitable and unavoidable.

It was not a question of if; it was a question of when. And this time it was going to be a nuclear war.

It's a M.A.D. World

The generation that came of age following the end of World War Two grew up with the unambiguously certain knowledge that their lives were going to be violently snuffed out in a thermonuclear fireball; probably sooner rather than later. It was accepted as a given that what had happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 was going to happen everywhere.

Over the next few weeks I want to explore the impact that had on popular culture, beginning with one of the many, many films of that period that attempted to portray the outbreak of nuclear war.

We Will All Go Together When We Go

In 1964, a film was released depicting a sequence of events leading to the outbreak of nuclear hostilities. It was made in the immediate aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis (when the world had come very, very close to an actual nuclear war) and featured a high profile cast working with a respected director.

No, not that one. The other one.

Fail Safe is the 1964 film that nobody saw, because everyone was too busy pointing and laughing at Peter Sellers in Dr. Strangelove.

Both films were released in 1964 and both films deal with the accidental deployment of nuclear weapons. But where Dr. Strangelove is an infantile comedy that relies on juvenile humour and ridiculously over-the-top performances (three of them by Peter Sellers) Fail Safe is a deadly serious film, directed by Sidney Lumet and starring (among others) Henry Fonda and Walter Matthau, plus (in their feature film debuts) Larry Hagman and Fritz Weaver.

The fact that Fail Safe was far less successful than Dr. Strangelove was not accidental. Worried that the release of Fail Safe would hurt his own film at the box office, director Stanley Kubrick (with the assistance of Columbia Pictures) filed a lawsuit against Sidney Lumet and his production company. Columbia Pictures was able to acquire the rights to the rival film, and ensured that Fail Safe wasn't released in cinemas until eight months after the (much wider and louder) release of Dr. Strangelove.

Critical reception of Fail Safe was overwhelmingly positive, and with good reason. It is an infinitely better film than Dr. Strangelove, featuring a plausible (and chilling) scenario and a very committed ensemble cast who give beautifully understated performances.

Walter Matthau (in the second of his three appearances in this current series of ours) plays a political analyst whose character has absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with Henry Kissinger. I don't know what made you say that.

And Larry Hagman shines in a very difficult role as the President's translator.

Ultimately, what makes Fail Safe so compelling is the urgency of the story it tells. The world had already been brought to the brink of all-out nuclear war in 1962 and the general feeling was that a scenario like the one depicted here was almost certain to happen, probably very soon. That sense of urgency is reflected by everyone in the production (on-screen and off) and the result is one of the darkest and most chilling Cold-War films ever released.

We will screen Fail Safe at 7.30 on Thursday, the 2nd of November at the Victoria Park Baptist Church.

Speaking of accidental deployment of (nuclear) weapons reminds me of the 1965 film The Bedford Incident with Richard Widmark at his finest, Sidney Poitier, always fine and a very nervous James MacArthur.

ReplyDeleteYes indeed; "The Bedford Incident" is a wonderful film, and also features a tiny part for a not-yet famous Donald Sutherland (as one of the junior medical officers). Sidney Poitier also cites it as the first film he ever appeared in where his skin colour is not a plot point.

DeleteThere were so many "Nuclear Apocalypse" films from that era; it was a subject of fairly urgent concern to everyone at the time! "On the Beach" is another wonderful (albeit very downbeat) example.

There were also several "post-apocalyptic" films made about what things might be like after the bombs have fallen. I would strongly recommend "The World, The Flesh and the Devil" (1959) as well as a very low-budget film directed by Arch Obler from 1951 called simply "Five" (which is the number of people left alive at the beginning of the film).