Down With... Reasonable Doubt

In 1998, the writer Peter Biskind published an exposé of mid-Century Hollywood entitled Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock 'N Roll Generation Saved Hollywood.

His thesis, in a nutshell, was that the collapse of the studio system in the 1950s left an opening for a younger, edgier generation of film-makers to rise to prominence, ushering in what Biskind clearly thinks of as Hollywood's "Golden Age".

Earlier generations of Hollywood film-makers had generally "worked their way up through the ranks" - learning the trade by actually making movies (either in Hollywood or in Europe, before they were forced out by the Nazis) but this new generation (which Biskind calls the "movie brats") were mostly graduates from film schools (Martin Scorsese; John Milius; Francis Ford Coppola) emerging into the film world as fully-formed directing auteurs. (Every year, the film schools turn out yet another generation of would-be directors. No one goes to film school with the dream of becoming a focus-puller, or a key grip. Those jobs are for everyone else.)

According to Biskind's reading of history, these new visionary film-makers were given unprecedented freedom to make movies without studio interference because the studios were, by this point, largely in the hands of accountants who knew nothing about film as an art form, and were mostly happy to leave these youngsters to their own devices. Thus we saw a generation of films being released in Hollywood that were violent, brutal, misogynistic and angry. Exactly what you would expect from a group of privileged white, male college graduates with inflated egos and no one looking over their shoulders. This Golden Age of Hollywood was eventually ruined (according to Biskind) by the unprecedented success of Jaws and Star Wars in the mid 70s, and the rise of the "Blockbuster".

Biskind's thesis was compelling, and has become the de facto take on mid-Century Hollywood for many (not all) observers of American cinema. It is unfortunate, therefore, that in order to make his case, Biskind felt the need to completely erase an entire generation of film-makers.

What is largely ignored by Easy Riders, Raging Bulls is that in between the end of the "studio" era and the rise of the "film graduate era" was a group of film-makers who came from a completely different background, and who were to have an enormous influence on American cinema and the way films were made for decades to come.

One of the (many) reasons why the Studio system failed in the 1950s was the rise of television in American households. This has been exhaustively discussed in almost every account of American popular culture, and it is certainly true that film attendance dropped significantly, in parallel with the rise of television ownership in the generation following the war.

But someone obviously had to produce content for all those televisions, and the vast majority of television drama of the 1950s was broadcast live.

Alongside all the game shows, news broadcasts and detergent commercials was a significant body of scripted drama, much of it extremely erudite, that was (for all intents and purposes) live theatre, written and rehearsed from scratch every week, then performed in front of the television cameras that would broadcast it to tens of millions of living rooms around the country, exactly as it was happening in the studio.

12 Angry Men may have been the theatrical film debut of Sidney Lumet, but by 1957 he was already a veteran of live television drama, which he had been directing for years before this. And he was by no means unique. John Frankenheimer, Robert Aldrich; Franklin Schaffner and William Friedkin (to name a few) all began their careers directing live television dramas, and they all were to have an enormous impact on Hollywood of the next several decades.

Unlike the younger "movie brat" film school graduates, these television-era directors were accustomed to working quickly and efficiently, often with severely limited resources. Because everything they did was live, they had to be stage directors and film directors simultaneously; guiding the actors through a performance in real time while also wrangling the television cameras, the lighting, the sound etc.

All of this discipline is readily apparent in 12 Angry Men.

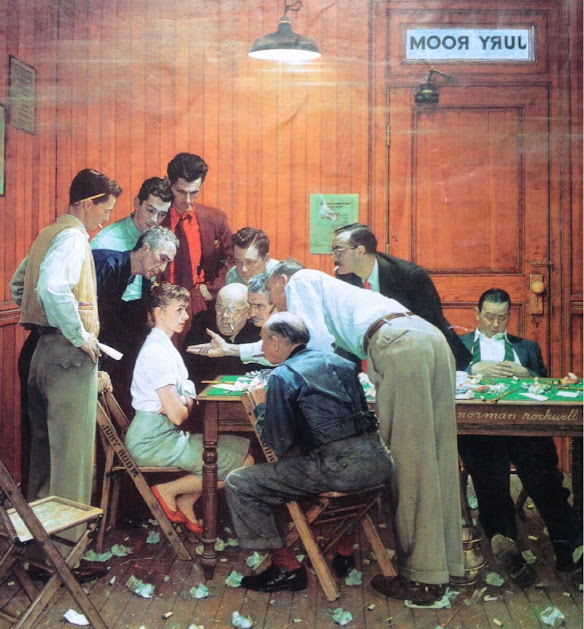

Originally written as a one-hour television drama for Studio One in 1954, Sidney Lumet's film version takes place almost entirely inside the sweltering jury room as the twelve jurors debate the minutiae of what at first glance appears to be an open-and-shut murder case.

Indeed, this film has become so influential that it is virtually impossible to tell any story about jury deliberations without making reference to 12 Angry Men (either deliberately or otherwise). Many prominent legal professionals (up to and including Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor) have cited 12 Angry Men as a major influence on their ultimate career path.

The film still stands today as a powerful examination of the American legal system (and the death penalty in particular). It may not be as noisy or as radical as the films of the "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls" generation, but it is, in its own, quiet way, extremely revolutionary.

We will screen Sidney Lumet's 12 Angry Men at 7.30pm on Thursday, the 22nd of June at the Victoria Park Baptist Church.

Comments

Post a Comment