Down With... Heresy

Okay, folks, this really is it. The time has come. The moment is now.

We have been running these film nights for over eight years, and in that time, it's safe to say that I have shown many different kinds of films. Some have been iconic classics, and some have been incredibly obscure. Some of them were silent films. A few were in 3D. In fact, we've shown pretty much every type of film by now: old films, new films and films from in between. French films, German films, even films for Halloween.

In all these years, however, there is something that I have consistently resisted, but have always wanted to show. I have just been waiting for the right moment.

This is the moment. The moment we've been waiting for.

(...and if you get the reference, you will know what I'm about to say.)

That's right, ladies and gents. On Thursday, the 30th of March, and for the very first time, I'm going to show an opera.

Down With... Lady Parts

So far, in our exploration of Cancel Culture, we have looked at various historical populist crusades against Integration; against Communism; against Evolution; against Witchcraft; even against Architecture. (One of these crusades is not like the others...)

But as the saying goes, there's no crusade like a Crusade (is that an actual saying, or did I just make it up?) and where there's a Crusade, there's an accusation of heresy.

So, without further ado, let's talk about Salome.

Salome, the biblical character, appears (but is not given a name) in the Gospel of Mark:

And when a convenient day was come, that Herod on his birthday made a supper to his lords, high captains, and chief estates of Galilee;

and when the daughter of the said Herodias came in, and danced, and pleased Herod and them that sat with him, the king said unto the damsel, Ask of me whatsoever thou wilt, and I will give it thee.

And he sware unto her, Whatsoever thou shalt ask of me, I will give it thee, unto the half of my kingdom.

And she went forth, and said unto her mother, What shall I ask? And she said, The head of John the Baptist.

And she came in straightway with haste unto the king, and asked, saying, I will that thou give me by and by in a charger the head of John the Baptist.

And the king was exceeding sorry; yet for his oath's sake, and for their sakes which sat with him, he would not reject her.

And immediately the king sent an executioner, and commanded his head to be brought: and he went and beheaded him in the prison,

and brought his head in a charger, and gave it to the damsel: and the damsel gave it to her mother.

A slightly streamlined, but fundamentally similar account appears in the Gospel of Matthew, where once again, Salome is only referred to as the "daughter of Herodias".

Her name (and a few other biographical details) comes from the Histories of the Jews by Flavius Josephus, published around 93 or 94AD.

Over the Centuries, Salome has become a popular figure in the visual arts; usually doing something fun and interesting with the head of John the Baptist.

But for our purposes this Thursday, things really get interesting when Oscar Wilde decided to write a play about Salome.

Oscar Wilde's Salomé was written in 1891 (in French) and received its first performance in 1896 (by which time Wilde was already serving his prison sentence for homosexual activity).

In England, the play was promptly banned, officially because it contained depictions of Biblical characters; something that was forbidden by the Lord Chamberlain's office. In practice, this restriction was hardly ever invoked. Handel's Messiah was a popular favourite then as now. Saint-Saens' Samson and Delilah had received a concert performance at Covent Garden in 1893, and local performances of Nativity Scenes and Passion Plays were never subject to police raids (well, hardly ever).

The truth is Salomé would have been banned no matter what. The Biblical connection was a convenient excuse, but it wouldn't have changed anything had the play been set in Ancient Egypt, or Colonial Boston, or the planet Venus.

Salomé is a play that is drowning in sexual perversion (sexual pathology might be a more accurate term) and it was deeply shocking to the late Victorian audiences who were both fascinated and repulsed by the tale of a young girl and her obsession with the prophet Jokanaan (or at least parts of him).

When the Canadian-born dancer Maud Allan gave private performances of Salomé in London in 1918, she was attacked in print by the right-wing MP Noel Pemberton-Billing. In an article headlined (and I swear I am not making this up) The Cult of the Clitoris, Pemberton-Billing accused Allan of being a member of a secret cabal of 37,000 lesbians who were operating in British society as German agents to undermine the war effort. (More about that on Thursday).

The version of Salome that I intend to show this week is actually not Oscar Wilde's original French version, nor is it the (very bad) English translation by Lord Alfred Douglas; it's Richard Strauss' opera of Salome, first performed in 1905. (I told you I'm showing an opera this week!)

Strauss had seen Wilde's Salomé in Berlin (in German) and had immediately thought it had the makings of a magnificent opera, which he then proceeded to write.

The text of his opera is essentially the German translation of the play, with no changes apart from a few edits. But the difference between the play and the opera is very striking. Where the play is very stylised, almost ritualised, it suddenly makes sense as an opera. It's still full of sexual pathology, and it's still deeply shocking, but as Anna Russell once said, "that's the beauty of grand opera; you can get away with anything as long as you sing it."

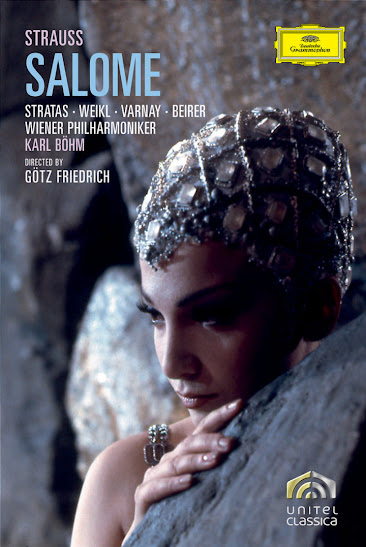

Although I was very tempted to screen the 1992 Covent Garden production of Salome (above) with Maria Ewing, directed by Peter Hall (the mother and father of actress Rebecca Hall, whom we just saw as Elizabeth Marston) I have ultimately decided to show a 1974 film version of the opera with Teresa Stratas. Maria Ewing gives a phenomenal performance, but the 1974 version is frankly the better film, and is also technically better (better sound, better image quality).

Whether as an opera, a play or a film, Salome remains an inflammatory and extremely sordid tale of obsession, sexual arousal and forbidden desire that is almost as shocking today as it was at the turn of the Century.

And the music is amazing.

We will be screening Salome at 7.30 on Thursday, the 30th of March at the Victoria Park Baptist Church.

(And don't worry, Salome; the Opera runs for an hour and forty minutes, so we won't be there all night! This isn't one of those operas that is meant for "that boring stretch between Leap Years".)

I hope your screening went well & that many new people were amazed by Strauss & Wilde. But for my money, the most amazing & shocking film interpretation of the play has to be Ken Russell's Salome's Last Dance. While he may not have been in Wilde's league, Russell was truly an original!

ReplyDelete--Paul Gillis