Music. Weaponised.

Part the First:

Where is the Music Coming From?

This Thursday (the 8th of December) I plan to screen the 1962 film version of Meredith Willson's Broadway classic, The Music Man.

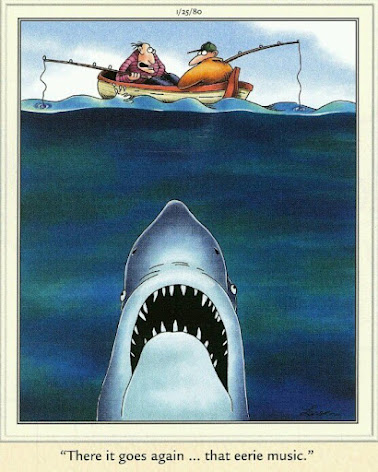

Before I get into that however, take a look at this cartoon:

Let's talk about film music for a moment.

Generally speaking, film music can be divided into two categories. The first of these is the music that occurs within the narrative of the film.

A character turns on the radio, and hears music.

A character starts playing the piano, and hears music.

A character walks into a spaceport bar where a weird alien jazz combo is performing, and hears music.

Film music of this type is what pretentious film scholars such as myself like to call diegetic music. This music exists within the universe of the film, and is real and audible to the characters in the story. In other words, it is music as we know it. The characters in the movie hear this music exactly as we hear music in the real world. Every note of music that we have ever heard in our entire lives is effectively our diegetic music.

Hitchcock was quite correct to wonder where diegetic music might come from in the middle of the ocean. That would be quite ridiculous; they're in a lifeboat. There wouldn't be any radios or cocktail pianos or jazz bands, so there wouldn't be any music, unless they happened to pick up a passing Nazi U-Boat commander with a good singing voice. But what are the chances of that?

There is, however, another type of film music. This is the music that forms what we usually think of as the soundtrack, or the background music.

A character bids an emotional farewell to his or her lover, and the music swells up.

A character unwittingly goes for a relaxing swim in shark-infested waters, and the music swells up.

A character contemplates his future as he gazes at a weird alien sunset, and the music swells up.

Unsurprisingly, those same pretentious film scholars like to refer to this type of music as (you guessed it) nondiegetic music. Nondiegetic music only works when we, the audience, understand that the music is audible to us but not to the characters in the film. The bathers in Jaws cannot hear the shark music, otherwise they would get the hell out of the water.

With nondiegetic music it doesn't matter where the music is coming from because it doesn't need to be explained by the narrative, any more than the cameras filming the scene need to be explained (as Hugo Friedhofer quite correctly pointed out to Hitchcock).

Nondiegetic music is there and not there simultaneously.

Usually it will be very obvious whether the music in a scene is diegetic or nondiegetic, unless the scene is played for laughs. (Yes, Mel Brooks, I'm thinking of you...).

Traditional cinema tends to be very naturalistic, and the presence of phantom, non-existent music can threaten that naturalism unless there is a very clear dividing line between music that the characters can hear, and music that they can't hear.

But what about musicals?

When characters in a musical spontaneously burst into song, is that music supposed to be diegetic or nondiegetic? What exactly are these characters supposed to be hearing when they are singing to each other?

Of course fictional characters have been singing to each other long before the advent of cinema. Stage musicals and operas all feature characters who express themselves in song - but stage performances don't have the same level of naturalism you tend to find in cinema, so the relationship of the music to the narrative is a little different. Opera in particular exists in a very stylised version of reality, where characters express themselves through music.

Measuring film music against opera isn't as ridiculous as it sounds, because the fundamentals of Hollywood film scoring were laid down by composers like Max Steiner and Erich Korngold, who had come directly from the late-romantic European operatic tradition. The language of Hollywood film music is explicitly operatic in both form and harmonic style. The biggest difference is that characters in Hollywood dramatic films don't usually sing to each other. This allows film-makers to draw a very clear dividing line between the (diegetic) characters and the (nondiegetic) music (unless you're Mel Brooks - see above).

Trying to label opera as diegetic or nondiegetic is fairly pointless, because the music in an opera cannot be separated from the narrative. When everybody is singing, the music is the narrative. With apologies to Marshall McLuhan, the medium is the music is the message.

Having said all that, The Music Man is a shining example of what can happen in a work of musical theatre when the status of music in the narrative is tampered with.

You thought I'd forgotten about The Music Man, didn't you?

Part the Second:

The Diegetic Paradox; or Where is the music coming from??

The Music Man tells the story of Professor Harold Hill, a travelling con artist who goes from town to town in the Central United States in 1912, passing himself off as a band leader. He sells musical instruments and uniforms with the promise of forming a boys' marching band, then scrams out of town before anyone can discover that he knows nothing at all about music.

This is very ironic, because music is not only Professor Hill's strength, it's his weapon.

Throughout the narrative, Harold Hill repeatedly uses music to his advantage by systematically and deliberately blurring the lines between diegetic and nondiegetic music.

In the early scenes, most of the musical numbers are explicitly built around a "diegetic" source.

Take the show-stopping opening scene for example, when a train-load of travelling salesmen tell each other their troubles. The whole scene is a (magnificent) musical performance, set to the rhythm of their moving train carriage. Actually, their conversation is the rhythm of the moving train carriage, in a theatrical conceit that was quite unlike anything Broadway audiences had seen or heard before.

A few scenes later, Marian the Librarian is having a conversation with her mother while giving a piano lesson in the family sitting room. She carries on the conversation while sounding out the notes of the keyboard exercise her student is trying to play. So far, so diegetic. Her mother replies, continuing the line of the piano exercise, and before anyone even realises what's happening, they're singing to each other.

And then, to really drive home the point, Marian does it again, with her student's second keyboard exercise.

In all of these instances, the songs are not diegetic (at least not in the "musical-within-a-musical" sense of a Busby Berkley film, for example) but they are "kick-started" by a diegetic source (the moving train carriage; the two piano exercises). Diegetic music causes the nondiegetic songs.

Enter Professor Harold Hill.

It very quickly becomes apparent that Professor Hill is uniquely able to "conjure" diegetic music out of nowhere. We get a glimpse of it when he whips the townsfolk into a frenzy over the (imagined) dangers of installing a pool table in the local billiards hall, but we really see it in its full glory when he hijacks a town meeting to sell everyone on the idea of a boys' band.

All by himself, and without any (diegetic) musical accompaniment, he manages to turn the entire town into a fantasy marching band. Everyone (apart from the very cynical Marian the Librarian) gets caught up in the illusion, marching around the gymnasium and then out into the street, carried away by the unforgettable sounds of a marching band that explicitly doesn't exist.

Except, of course, it does exist.

We can hear it, sitting in the audience watching the musical, just as we can hear any nondiegetic musical score that accompanies a dramatic scene. But the characters in the scene aren't supposed to hear it. It's almost as if Harold Hill has made the nondiegetic music audible to everyone else in the scene.

As the story progresses, Hill does this over and over again. When the members of the school board pester him for his (non-existent) credentials, he neutralises them by promptly transforming them into a barbershop quartet.

Later, he does something similar with a group of gossipy housewives. And then there's the massive, all-out, song-and-dance extravaganza (with full company) about... being quiet in a library?

In every one of these scenes, Harold Hill is skilfully and deliberately erasing the boundaries between diegetic and nondiegetic music. It's almost as if he has learned how to weaponize the soundtrack.

Marian the Librarian is the only one in the town who can see (hear) what he is doing, but crucially she is also the first person to realise what a positive effect he is having on the community, and on her son in particular.

Brother. (Sorry, did I say "son"? I meant "brother". Of course he's her brother. Why on earth would you think he's her son? I don't know what made you say that.)

It's eventually Marian who perfectly expresses Harold's ability to make the nondiegetic music audible to everyone on demand:

There were bells on a hillBut I never heard them ringingNo, I never heard them at all'Til there was you

[...]

There was love all aroundBut I never heard it singingNo, I never heard it at all'Til there was you

The turning point for Harold Hill is when he stops, probably for the first time in his life, and actually listens to someone else's music. This is shown explicitly: he suddenly stops himself in the middle of a chorus of "76 Trombones" and begins to sing Marian's song. After a lifetime of bending others to his music, he is suddenly aware of music that is coming from someone else.

The resolution to the story is also perfectly in keeping with this diegetic/nondiegetic paradox, and it will be very familiar to anyone who has ever witnessed a primary school concert attended by a gaggle of over-enthusiastic parents.

Fortunately for everyone in River City, Harold Hill is a very benign con artist. Everything he does makes the town a better place - thankfully - because his technique of essentially "tuning everyone in" to the nondiegetic music would make him a very dangerous villain, had he chosen to use his powers less benevolently.

Don't believe me? Allow me to introduce you to Harold Hill's Grandmother and Great-Grandfather.

Part the Third:

Meet Harold Hill's Ancestors, or Where the Music Came From

I have already said that it's pointless trying to label the music in an opera as diegetic or nondiegetic, because opera Doesn't Work That Way.

However, there are a couple of very notable exceptions, and Harold Hill's character in The Music Man owes a great deal to those exceptions.

The first of these is Don Giovanni, Mozart's immortal re-telling of the story of Don Juan.

Don Giovanni was the second of Mozart's three collaborations with the librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte. The first of those, The Marriage of Figaro, features a moment when Figaro, singing of his plans to out-manoeuvre his somewhat out-of-control employer, says,

"You may go dancing, but I'll play the tune!"

(It sounds a lot better in Italian, but I'm going to stick with English for the purpose of getting through this manifesto.)

Figaro's comment could almost have been the "tag-line" for Don Giovanni, if they had tag-lines in 1787 (spoiler alert: they didn't). It also fits The Music Man rather well.

Don Juan of course is the oft-retold story of a dashing and over-sexed nobleman who cavorts across Europe, seducing and deflowering women wherever he finds them until the statue of a man he murdered comes to life and drags him to hell as punishment for all that extra-marital sex.

In the hands of Mozart and Da Ponte, Don Giovanni is no beloved scoundrel or courtly rogue; he is a rapist and a murderer who is so powerful that it takes a supernatural intervention to finally bring him down. Certainly no one else in the opera is strong enough to stop him (and quite a lot of them have a go at it).

But what makes Don Giovanni's character so interesting (in the context of this discussion) is his weapon of choice, which is effectively music itself.

Consider the first appearance of Donna Elvira in Act I. Elvira has arrived in town incognito, searching for the man who seduced and abandoned her. (I always imagine that Elvira is pregnant, which explains why she is so desperate to track down Don Giovanni and re-unite with him, even after learning what kind of monster he is. It also explains her violent mood swings throughout the opera. But I digress...)

As she arrives, Giovanni and his servant Leporello hide in the wings while Elvira sings her initial aria. By convention, opera arias are internal monologues, giving voice to the innermost thoughts of the character. Like Shakespearian soliloquies, they are heard by the audience, but not by other characters in the narrative. In effect, they are nondiegetic.

Except that Don Giovanni can apparently hear Donna Elvira.

He listens to her, and reacts to what she is singing. There is no indication that she can hear him (and there is no indication that Leporello can hear Elvira, even though he and Giovanni are standing right next to each other). It's as if Giovanni is hearing the music the way the audience is hearing it. He's listening to a nondiegetic aria.

Remind you of anyone?

This happens again and again throughout the opera. When Giovanni tries to seduce the peasant girl Zerlina, he asks for her hand, offering to take her to a place where she will say "yes". (Many English translations replace "yes" with "I do" but Giovanni is not discussing marriage with Zerlina; he has something rather more.... elemental... in mind.) Zerlina grapples with herself over the question of whether or not to go with him. Throughout the duet, Giovanni sings to Zerlina, but Zerlina sings to herself. It's almost as if Don Giovanni has hijacked Zerlina's internal monologue. She may be singing to herself, but the music in her head is his music. (Remember Figaro? "You may go dancing, but I'll play the tune...") In a very real sense, Don Giovanni is using music to violate Zerlina - which is of course exactly what he has in mind.

The most dramatic use of Giovanni's musical power occurs at the end of Act I, when he uses music to separate the various characters from each other, in order to get Zerlina off by herself. The scene is a festive celebration with on-stage musicians (diegetic) and Giovanni gets different characters to start dancing to three completely different pieces of music (in three different time signatures) simultaneously. He is then able to scurry off with Zerlina, and no one else on stage is able to stop him because they are each trapped in their own private musical realities. Just like Harold Hill trapping the school board in a barbershop quartet, they are all quite literally dancing to his tune.

Don Giovanni's command of the musical score is not seriously challenged until well into Act II when the statue that will eventually kill him first comes to life. (Do I really need to worry about spoiler alerts for a 235-year-old opera?) Giovanni and Leporello are talking to each other (in recitative, which is as close to spoken dialogue as it gets in an opera like this) when they are interrupted by the singing voice of the statue, accompanied by on-stage trombones (no, not 76 of them; hush now). The trombones are not part of the instrumental texture of the score, and had not been heard in the opera before this moment. When Don Giovanni speaks again, it is in recitative, as before. The statue again answers in song, again with trombones. The effect is of a "voice from another world". This is the first moment in the entire opera when something other than Don Giovanni has control over the music, and it's his first intimation that there's a musical force out there that's bigger than he is.

The moment is directly paralleled in The Music Man when Harold truly hears Marian's music for the first time. Except of course, Marian does not then proceed to drag Harold down to the pits of hell. Don Giovanni is a lot nastier than Harold Hill, and consequently his ending is a lot messier.

But then what did you expect in an opera; a happy ending?

(Sorry, someone had to say it.)

Harold Hill and Don Giovanni are not the only characters to have had this impossible relationship with their own music. To meet the third member of the meta-diegetic trio (I just made that up. Do you like it?) we need to look to Paris in 1875 (88 years after Don Giovanni and 87 years before The Music Man).

Like Don Giovanni, George Bizet's Carmen presents a central operatic character who uses music as a weapon. If anything, the effect is more pronounced in Carmen because Bizet uses music mixed with spoken dialogue, a technique that was decidedly at odds with operatic conventions of the era.

In Act I, Carmen is arrested after attacking another girl with a knife. The captain of the guard questions her with spoken dialogue, but Carmen's responses are sung. The captain is unimpressed, and continues his interrogation in prose, explicitly admonishing Carmen for singing to him. ("Spare us your songs"). He eventually orders her to be taken away under guard ("Since you adopt that attitude, you'll sing your song to the prison walls").

She is left (tied up) in the company of Don José, with whom she has a brief (spoken) conversation before he commands her not to speak ("Don't talk to me any more! You hear me? Say no more. I forbid it!").

Without missing a beat (quite literally) she begins to sing, and we get to witness Don José getting seduced before our very ears. He begs her to stop ("Stop! I told you not to talk to me!") but his plea to her is sung, not spoken. Her response ("I'm not talking to you, I'm singing to myself") is almost redundant. The moment he began singing, he was doomed. Carmen's diegetic song has become Don José's nondiegetic music. This is Don Giovanni and Zerlina all over again, and it prefigures Harold Hill transforming an entire town into a nondiegetic marching band (and a school board into a barbershop quartet).

Carmen even has a moment when her mastery over the musical score is challenged; just like Giovanni and his statue, or Harold and his librarian. Carmen is spending a moment alone with Don José, and gives him a private dance, accompanying herself on the castanets (providing her own diegetic music). As she dances, Don José is distracted by military trumpets in the distance, sounding the retreat. When he draws her attention to them, she is initially thrilled ("It's dismal dancing without an orchestra. And long live music that drops on us out of the skies!") but she becomes angry when she realises José intends to return to barracks; effectively choosing the bugles over her. Her reaction is one of jealousy. She essentially accuses José of being unfaithful to her; of fooling around with other soundtracks, in effect. ("I sang! I danced! I believe, God forgive me, I almost fell in love! Taratata! It's the bugle sounding! Taratata! He's off! He's gone!")

Carmen need not have worried. José forgets all about the trumpets and stays with her - although he does eventually kill her a lot. When she dies, it is not to the accompaniment of diegetic trumpets or her own diegetic song; it is against the diegetic victory music of the bullfighter Escamillo, with whom she had genuinely fallen in love. Don José's defeat is total and humiliating: he can't even get Carmen into a soundtrack of his own while he's murdering her.

Part the Finalth:

Where the Music Comes From

The Ancient Greeks had a theory that the celestial bodies of the universe all emitted sounds as they moved around the heavens.

These sounds collectively made up the perfect music of the universe; the Musica Universalis (as it was called in the 16th Century, when the theory was revived) or the "Music of the Spheres". Since the heavenly bodies were presumed to move in perfect harmony, it was postulated that their movement would produce actual perfect harmony; a perfect, beautiful music that was all around us all the time, but inaudible to mere mortal humans.

That sounds an awful lot like the definition of a nondiegetic soundtrack: a piece of music that is all around us all the time, but cannot be heard by those of us who actually play out this little drama we call "life".

What might that music sound like? Suppose there really was some sort of "perfect" soundtrack to our lives, just beyond our perception, but always there, accompanying everything we do or say.

What would it do to us if we were somehow able to listen to our own soundtrack in real time? Would it make us Don Giovanni? Or Carmen? Or Harold Hill?

I should say that absolutely none of this has anything to do with the reason why I am screening The Music Man this Thursday. I am screening it for two reasons: first, it is a magnificent musical that deserves to be seen and heard.

Second, it feeds directly into the series I plan to begin in the New Year. More about that in due course...

In any event, I plan to show The Music Man at 7.30pm on Thursday, the 8th of December at the Victoria Park Baptist Church.

Thanks for taking the time to read all this!

Brilliant

ReplyDelete